Where’s the water, and why the ice?

VIMS professors help explain recent cold spell, low tides

Wondering where all the water went? You’re not alone. People around Chesapeake Bay have been noticing persistently low water levels in tandem with our recent cold spell.

Indeed, in an era when some of the most consistent environmental concerns are sea-level rise and global warming, almost two weeks of low tides and chilly temps has raised a host of questions, as well as concerns among vessel operators, certain anglers, and oyster growers. The latter worry about potential mortality among oysters exposed to below-freezing air temperatures during low tide.

Dr. John Boon, VIMS emeritus professor and tidal expert, says the answers to these questions lie in the complex interplay among the sun, moon, and Earth, as well as our planet’s own land, ocean, and atmosphere.

In regard to water levels, Boon says “We’re near the low in the seasonal cycle right now because it’s winter and water contracts when it’s colder.” He says recent tides have also been of relatively low magnitude due to the regular monthly variations in the relative alignment of the Earth, moon, and sun.

But Boon says a more significant factor in explaining the low water levels is a pattern of persistent northerly winds, which act to push water out of the Bay. For example, data from NOAA’s York River buoy shows that winds blew almost exclusively from within 30 degrees of north between December 30th and January 7th.

VIMS emeritus professor Carl "Woody" Hobbs notes that barometric pressure may have also contributed to the low water levels. "High barometric pressure depresses water levels just as low pressure increases storm surge," he says. "The very clear, very cold weather we just experienced often occurs with high pressure."

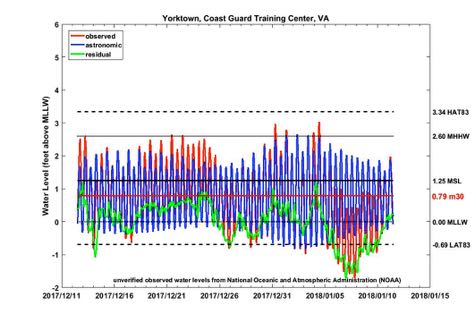

Boon says other broader meteorological factors are also in play. That’s apparent in the monthly mean sea level (MMSL) values shown in the Tidewatch charts he developed to help people keep track of water levels in the Bay and adjacent coastal areas.

For example, the current MMSL value for the tide gauge at the York River Coast Guard station is 0.79 feet, almost half a foot lower than the station’s current 1.25-foot value for mean sea level.

“The MMSL numbers for December are a bit lower than usual,” says Boon. “In the last 10 years at Norfolk only 3 Decembers have come in below this year's low.” The recent spell of northerly winds is likely part of the reason, but Boon notes that similar December MMSL lows are showing up in other regions as well.

The widespread occurrence of these low MMSL values makes Boon think they’re most likely due to year-to-year changes in regional ocean-atmosphere interactions such as El Niño or the North Atlantic Oscillation, “That's inter-annual variability for you,” he says.

Cold spell

By bringing cold Arctic air unusually far south, the persistent northerly winds also help explain the recent cold spell, which saw temperatures fall below daily mean high and low values almost continuously between December 27th and January 8th.

Also contributing to the chill was the passage of winter storm “Grayson.” The counter-clockwise circulation of this uncommonly intense coastal low-pressure system helped drive the northerly winds, and moreover brought significant snow to areas all along the U.S. Eastern seaboard. The snow accentuated the cold temperatures by reflecting the already weak winter sunlight.

Ironically, there is mounting evidence that global warming may be contributing both to powerful winter storms like Grayson and cold spells in the eastern U.S. The reasoning here is that the significant warming observed in the Arctic during the last few decades is reducing the temperature contrast between polar and temperate areas. This in turn decreases the strength of the jet stream, which makes it more likely to develop persistent meanders that can steer still relatively cold Arctic air far south.

Ironically, there is mounting evidence that global warming may be contributing both to powerful winter storms like Grayson and cold spells in the eastern U.S. The reasoning here is that the significant warming observed in the Arctic during the last few decades is reducing the temperature contrast between polar and temperate areas. This in turn decreases the strength of the jet stream, which makes it more likely to develop persistent meanders that can steer still relatively cold Arctic air far south.

"Cold air masses that used to be held more tightly in the polar region are now able to reach mid-latitudes like water from a broken dam," says Boon.

Another ironic factor in regards to the recent cold spell is that it was so perceptible exactly because recent winters have been so warm. In other words, cold spells like this used to be much more common, and thus much less remarkable.

Evidence for this long-term warming trend comes from observation of both air and sea temperatures; several long-serving and emeritus professors at VIMS corroborate the trend with anecdotal accounts. Their most notable memory is the winter of 1978-79, when ice covered not only Chesapeake Bay’s smaller tidal creeks, but its larger tributaries and mainstem as well. Hobbs, who began his career at VIMS as a graduate student in 1971, clearly remembers an aerial resupply mission that winter to Tangier Island near the Virginia-Maryland border, which was completely surrounded by ice and thus unavailable for resupply by ship.

“Cold winters used to be much more common,” says Hobbs. Climate data back him up.