Study shows taller reefs in large sanctuaries are key to oyster restoration

A 5-year study of oyster-restoration techniques in Chesapeake Bay shows that taller reefs in an extensive network of large sanctuaries is critical for re-establishing self-sustaining populations of native oysters.

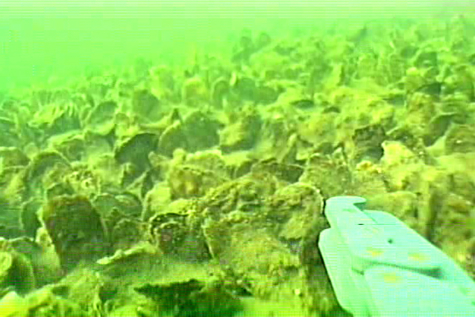

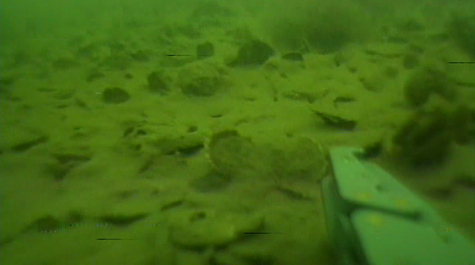

The study, to appear in the July 30th issue of Science Express, was conducted by Virginia Institute of Marine Science graduate students David Schulte, Russ Burke, and professor Rom Lipcius. They compared oyster abundance and growth on reefs built to stand 10-18 inches above the seafloor with reefs that rise only 3-5 inches.

The US Army Corps of Engineers constructed the reefs in 2004 by placing old oyster shells in 9 discrete sets of reefs covering more than 80 acres in the Great Wicomico River, a small Chesapeake Bay tributary that lies between the Rappahannock and Potomac rivers and is known for having much higher recruitment than other areas in the Bay. Harvesting of oysters on these sanctuary reefs is permanently prohibited.

Sampling by the VIMS team in 2007 using oyster patent tongs and underwater video showed that the taller Wicomico reefs had four times as many oysters as the shorter reefs, and that the oysters on the taller reefs were bigger and faster growing than those growing closer to the bottom. All the oysters grew from larvae released by nearby wild oysters.

The taller reef areas held the highest densities of oysters ever recorded on a restored oyster reef in the Bay, more than 1,000 oysters per square meter, compared to 250 oysters/m2 on the shorter reefs. Pre-restoration surveys of the study area recorded fewer than 2 oysters/m2. Chesapeake Bay reefs that are open to harvest typically hold from 2-11 oysters/m2.

The Great Wicomico’s re-established population, which the researchers estimate at 184.5 million oysters, is the largest of any native oyster population worldwide. The restored population, which exists on 86.5 acres of reefs, is roughly equivalent to the entire oyster population on all of Maryland's 270,000 acres of public oyster grounds. The authors calculate that it is 57-times larger than the pre-restoration population; far exceeding the Chesapeake Bay Program’s previously unachieved restoration goal of a 10-fold increase of the 1994 baseline by 2010.

The authors say the taller reefs are successful because they expose their oysters to stronger currents, which sweep away sediments that can otherwise clog the delicate filters that oysters use to feed. The currents also provide a steady stream of food, which promotes rapid growth and helps the oysters better resist the diseases that purportedly kill most Bay oysters before they reach their second year, though evidence is mounting that oysters can develop disease resistance if provided with adequate reef structure.

The higher quality reefs also attract higher numbers of oyster recruits, increasing the chances they will be self-sustaining over a long period of time.

“Adding several inches to the height of a reconstructed reef provides a ‘jumpstart’ that allows the oysters to grow, reproduce, and begin to form a self-sustaining reef community,” says Schulte.

Importantly, the taller reefs appear to be growing fast enough to outpace chemical dissolution, breakdown by other organisms, and burial by the turbid Chesapeake’s abundant sediments. According to the authors, these forces have short-circuited previous efforts to restore oysters in Chesapeake Bay and elsewhere, by precluding the growth of the vertical, cohesive framework that forms the foundation of a healthy oyster reef.

They also credit the reefs’ continuing upward growth to the absence of fishing pressure—notably tonging and power dredging. In addition to removing the uppermost layer of living oysters, these methods destroy the underlying shell layers that comprise the reef framework.

Lipcius says “Our results suggest that oyster reefs exist in two alternative states, one a heavily-sedimented, degraded state and the other a vertically-accreting, elevated reef with abundant oysters, which provides a positive feedback to reef integrity.”

The taller reefs of the Great Wicomico have persisted and, more importantly, thrived for nearly 5 years, says Schulte, well past the typical longevity of failed oyster reefs. “These ‘high-relief’ reefs are gaining shell material and establishing oyster densities at rates previously unrecorded on native oyster restoration projects.”

He adds that the vertical growth and cohesiveness of the taller Wicomico reefs show that they are “coalescing into the historic, natural oyster-reef architecture typical of pre-exploitation reefs.“

Exploitation through harvesting of meat and shells has devastated native oyster populations around the world, including those in North America, Europe, and Australia. Chesapeake Bay’s oyster population currently stands at less than 1% of its historical abundance.

“Although disease will kill some oysters in the Great Wicomico, the recent development of disease tolerance in oysters on sanctuary reefs of lower Chesapeake Bay bodes well for the long-term persistence of this population and the ecosystem benefits it provides,” adds Schulte.

Preliminary results from the team’s survey of the reefs in winter 2009 show that the high-relief reefs continue to develop and harbor more than 1,000 oysters/m2, most of which are adults. Further, recruitment in the Great Wicomico River appears to have been enhanced, as evident on hard-bottom habitats throughout the system. Consequently, these reefs, which are now 5 years old, are not degrading and are developing into the robust reefs of centuries past.

The authors contend that the study “validates ecological restoration of native oyster species,” and that “similar approaches with other natural and artificial reefs could lead to recovery of the native oyster throughout North America, as well as other ecosystems worldwide.”