VIMS to help restore marine life to seaside bays

Researchers with the Virginia Institute of Marine Science will collaborate with public and private partners on a new effort to restore oysters, seagrass, and bay scallops to the Commonwealth’s seaside bays.

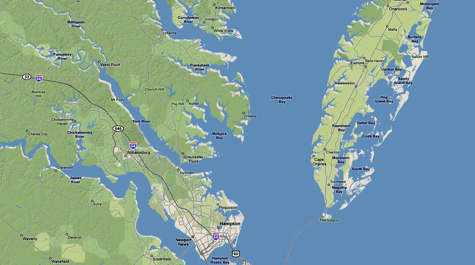

The $2 million, 18-month project is a partnership between VIMS, The Nature Conservancy of Virginia, the Virginia Marine Resources Commission, and the Virginia Coastal Zone Management Program. Restoration efforts will take place within The Nature Conservancy’s Virginia Coast Reserve, a 38,000-acre coastal wilderness that runs more than 60 miles from the Maryland border to the mouth of Chesapeake Bay.

"Restoring our marine environment is of critical importance and this project should yield wide-ranging benefits for many decades to come,'' says L. Preston Bryant, Jr., Virginia Secretary of Natural Resources. "I'm grateful for the hard work done by so many people—The Nature Conservancy, NOAA, VMRC, VIMS, and VCZM—on this cooperative effort. This truly is a landmark initiative."

The restoration partnership will restore 30 acres of native oyster reefs at 15 sites; plant 100 acres of seagrass; and re-introduce 2.4 million juvenile bay scallops to the restored seagrass meadows.

Mark Luckenbach, Director of VIMS’ Eastern Shore Laboratory in Wachapreague, says “This integrated restoration program will greatly accelerate our collaborative efforts to restore these valuable coastal resources, which are critical not only to the ecological health of the coastal bays, but to the economic health of the region’s seafood industry.”

VIMS professor Bob Orth adds “This project allows us to build on the success we’ve had with seagrass restoration in the Virginia coastal bays during the last decade, and now allows us to embark on a truly historic attempt to re-introduce the bay scallop, which supported a commercial fishery in the early 1900s but was completely wiped out in the 1930s by an eelgrass disease and the 1933 hurricane.”

During the last 8 years, with support from VCZM’s Seaside Heritage Initiative, researchers with Orth’s Submerged Aquatic Vegetation (SAV) program have broadcast more than 25 million eelgrass seeds into 207 acres of coastal lagoons along Virginia’s Atlantic shoreline. Growth by natural seed dispersal from these planted areas has now spread across 2,430 acres.

Seagrass plays an important role in helping keep water clean, by knocking down and absorbing sediment. Seagrass also serves as a nursery for wildlife, such as finfish, clams, crabs, and other shellfish, including scallops.

Luckenbach cautions that the project represents a first step toward restoration of the bay scallop. “The funding will help us accelerate the initial steps,” he says, “but it will take at least a decade to restore a viable scallop population to the seaside bays.”

Restoration plans call for the production of 400,000 hatchery-reared scallops for planting in 2009. Production will increase in 2010 to a minimum of 2,000,000 scallops. The scallops will be reared in facilities at VIMS’ Eastern Shore Lab, using brood stock from North Carolina.

VIMS Professor Ken Moore will monitor water quality in and around the restoration area, both to assess program success, and to identify other sites with water quality sufficient to support future restoration efforts. He will work with Dataflow, a high-tech sensor that can measure temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, turbidity, and other parameters every two to three seconds while being towed behind a research vessel at speeds of up to 25 knots. Previous work with Dataflow shows water in the coastal bays to be slightly cooler and clearer than in Chesapeake Bay, allowing eelgrass to spread rapidly in the coastal bays’ vast, shallow stretches.

The restored oyster reefs will be split between “no-harvest” and “rotational-harvest” zones, following the recommendations of the Virginia Blue Ribbon Oyster Panel. The no-harvest sanctuaries will provide juveniles to surrounding areas for future commercial harvest. The rotational zones will be opened to harvest every three years.

Funds for the “Virginia Seaside Bays Restoration Project” come through NOAA as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. The funding will provide 55 jobs in the Commonwealth for the duration of the project.