Loss of coastal seagrass habitat accelerating globally

First comprehensive analysis shows 58% of seagrass meadows in decline

An international team of scientists warns that accelerating losses of seagrasses across the globe threaten the immediate health and long-term sustainability of coastal ecosystems. The team has compiled and analyzed the first comprehensive global assessment of seagrass observations and found that 58 percent of world’s seagrass meadows are currently declining.

The assessment, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shows an acceleration of annual seagrass loss from less than 1 percent per year before 1940 to 7 percent per year since 1990. Based on more than 215 studies and 1,800 observations dating back to 1879, the assessment shows that seagrasses are disappearing at rates similar to coral reefs and tropical rainforests.

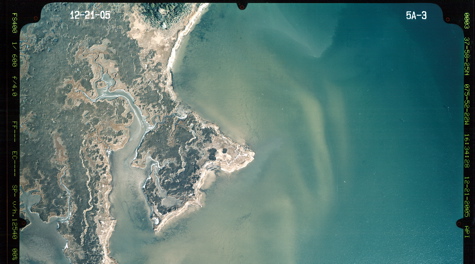

The research team, which includes professor Bob Orth of the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, estimates that seagrasses have been disappearing at the rate of 110 square kilometers (42.4 square miles) per year since 1980 and cites two primary causes for the decline: direct impacts from coastal development and dredging activities, and indirect impacts of declining water quality.

Orth says “While the loss of seagrasses in coastal ecosystems is daunting, the rate of this loss is even more so. With the loss of each meadow, we also lose the nursery habitat they provide to the fish and shellfish. The consequences of continuing losses also extend far beyond the areas where seagrasses grow, as they export energy to other ecosystems including marshes and coral reefs.”

“A recurring case of ‘coastal syndrome’ is causing the loss of seagrasses worldwide,” said co-author Dr. William Dennison of the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. “The combination of growing urban centers, artificially hardened shorelines, and declining natural resources has pushed coastal ecosystems out of balance. Globally, we lose a seagrass meadow the size of a soccer field every thirty minutes.”

“With 45 percent of the world’s population living on the 5 percent of land adjacent to the coast,” adds Orth, “pressures on remaining coastal seagrass meadows are extremely intense. As more and more people move to coastal areas, conditions only get tougher for seagrass meadows that remain.”

Seagrasses profoundly influence the physical, chemical, and biological environments of coastal waters. A unique group of submerged flowering plants, seagrasses provide critical habitat for aquatic life, alter water flow, and can help mitigate the impact of nutrient and sediment pollution.

One ray of hope for seagrasses comes from the success Orth and his team is having restoring seagrasses to Virginia’s coastal bays. The incredible speed with which seagrasses are spreading from seeds placed in these bays during the last decade shows how quickly seagrasses can rebound when water quality conditions do not jeopardize the plants’ survival.

The article “Accelerating loss of seagrasses across the globe threatens coastal ecosystems,” appears in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Early Edition on June 29. The article was authored by 14 scientists from the United States, Australia and Spain, including Drs. Michelle Waycott (lead author), Carlos Duarte, Tim Carruthers, Bob Orth, Bill Dennison, Suzanne Olyarnik, Ainsley Calladine, Jim Fourqurean, Ken Heck, Randall Hughes, Gary Kendrick, Jud Kenworthy, Fred Short, and Susan Williams.

The assessment was conducted as a part of the Global Seagrass Trajectories Working Group, supported by the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS) in Santa Barbara, California, through the National Science Foundation.