VIMS receives major grant to maximize future health of Bay

Project will identify key social and ecological factors for sustainability

Sea level has been rising in the Chesapeake Bay region for thousands of years, since the end of the last Ice Age. The difference today is that the rate of sea-level rise is accelerating, and millions of people and billion of dollars in property occupy the Bay’s shifting shoreline.

Now, a grant of $941,590 from the National Science Foundation to a multi-institutional team headed by researchers at William & Mary’s Virginia Institute of Marine Science will fund a 4-year effort to identify how policymakers and coastal residents can best respond to rising seas in order to maximize human welfare and Bay health. The project also involves partners from Old Dominion University and the University of Georgia.

Dr. Carl Hershner, project lead and director of the Center for Coastal Resources Management at VIMS, says “Our research will examine the potential for achieving sustainability in coastal systems where natural resources are impacted by both climate change and human responses to climate change.”

Dr. Donna Marie Bilkovic, a CCRM colleague and co-leader, adds “We’re talking about managing a resource that we know is under significant pressure and probably destined to decline dramatically in the next century. The question is can we in the interim do things in our management programs that will sustain at the highest possible level the ecosystem services that coastal resources provide.”

The research will proceed on two inter-related fronts: field studies and development of a suite of computer models that integrate and simulate the interplay between human decisions and the environment.

The field studies—led by Bilkovic and W&M biology professors Randy Chambers and Matthias Leu—are designed to fill gaps in scientists’ understanding of how marshes and living shorelines influence ecological processes—for example by trapping sediments, reducing wave action, and potentially storing carbon—as well as how they affect the distribution and survival of fish, birds, turtles, and other marine species. Living shorelines are now the recommended alternative for stabilizing tidal shorelines in the Commonwealth.

The field studies—led by Bilkovic and W&M biology professors Randy Chambers and Matthias Leu—are designed to fill gaps in scientists’ understanding of how marshes and living shorelines influence ecological processes—for example by trapping sediments, reducing wave action, and potentially storing carbon—as well as how they affect the distribution and survival of fish, birds, turtles, and other marine species. Living shorelines are now the recommended alternative for stabilizing tidal shorelines in the Commonwealth.

On the modeling front, Hershner says, “By modeling how a shoreline property owner responds to rising waters—whether they do nothing, build a bulkhead, or create a living shoreline—and then modeling the ecological consequences of their decision and the actions of policymakers, we’ll be able to discover opportunities and options for best managing the combined human and natural system.”

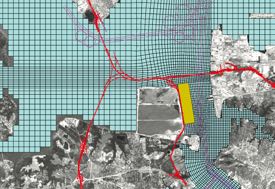

Leading the modeling effort are VIMS professors Jian Shen and Joseph Zhang, who have been instrumental in developing and refining two state-of-the-art computer models—HEM3D and SCHISM. These can simulate the movement of water and sediment in fine detail within Chesapeake Bay and along its highly convoluted shoreline, and have the added benefit of being open to contributions by other members of the international modeling community.

Leading the modeling effort are VIMS professors Jian Shen and Joseph Zhang, who have been instrumental in developing and refining two state-of-the-art computer models—HEM3D and SCHISM. These can simulate the movement of water and sediment in fine detail within Chesapeake Bay and along its highly convoluted shoreline, and have the added benefit of being open to contributions by other members of the international modeling community.

Providing insight from the social sciences are Sarah Stafford, professor and director of Public Policy Program at W&M, and Shana Jones, former director of the Virginia Coastal Policy Clinic at W&M Law School and now a faculty member in the Carl Vinson Institute of Government at UGA. Stafford says, “VIMS’ shoreline-projects database gives us an unparalleled opportunity to examine the relationship between coastal conditions and management decisions by property owners.” The database, developed through VIMS’ role in shoreline permitting in Virginia, provides a record of every shoreline project undertaken in the Commonwealth since 1976.

The benefits of effective management extend far beyond the shoreline. “Good management decisions can allow shoreline marshes to continue to provide ecosystem services such as supporting fisheries, improving water quality, and reducing coastal erosion,” says Hershner. “That in turn affects the entire Bay, with benefits for both marine life and coastal and inland residents.”

Building on existing resources

In addition to VIMS’ shoreline-projects database, the newly funded project also builds on VIMS’ shoreline inventory, in which CCRM researchers have mapped every foot of Chesapeake Bay’s 11,684-mile shoreline—either by motoring along in small vessels or poring over high-resolution aerial photographs. The resulting database—available as an interactive online map—characterizes Bay “shorescapes” in terms of shoreline type (e.g., whether natural marsh or beach, breakwater, bulkhead, jetty, riprap, or living shoreline); attributes of any shoreline banks (height, stability, and vegetative cover); land use (e.g., agricultural, forested, residential, industrial); and other onshore and near-shore features.

Says Bilkovic, “One of the very exciting aspects of this cross-disciplinary project is that we’ll be able to synthesize decades of monitoring data collected from both natural and human systems into a framework that can inform coastal sustainability. Our detailed record of shoreline-management activities, tidal-marsh distribution and change, and sea-level rise impacts on wetland resources are key to our plan to examine and model decision-making by property owners, and how those decisions affect continued provision of ecosystem services.”

The results of the project will also be relevant outside the Commonwealth and Bay waters. “Our findings should have relevance not only in Virginia but everywhere private property owners are in a position to balance private risk reduction and environmental impacts,” says Hershner.

The results of the project will also be relevant outside the Commonwealth and Bay waters. “Our findings should have relevance not only in Virginia but everywhere private property owners are in a position to balance private risk reduction and environmental impacts,” says Hershner.

NSF Coastal SEES

The current project is funded under NSF’s Science, Engineering and Education for Sustainability program, or SEES, and builds on a previous SEES “incubator” grant that allowed the research team to test the feasibility of their modeling approach before committing additional resources.

“In our incubator project, says Hershner, “we examined connections between human activities and natural systems in Chesapeake Bay, which is widely seen as the site of some of the most intense human-natural system interactions on the planet.”

NSF says the Coastal SEES program seeks to identify and fund work at the frontiers of science and engineering, specifically to better understand the connections between human activities and natural systems within coastal systems, with a goal of informing societal decisions about use of these systems for economic, aesthetic, recreational, research, and conservation purposes.