Input from end-users shapes planning tool

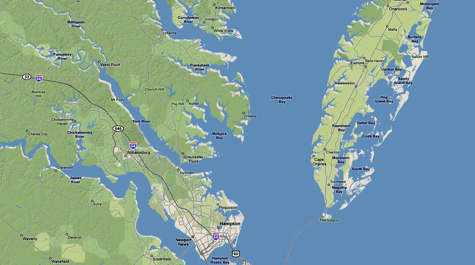

On a recent rainy afternoon, more than 15 community planners, scientists, and environmental managers met to preview a draft of a new tool aimed to improve the condition of Delmarva’s coastal bays. Researchers from Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia have spent two years developing the most recent version of the tool as part of the Delmarva Modeling Project.

The September 24 workshop at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science's Eastern Shore Lab in Wachapreague, VA, was the second opportunity for planners and managers to provide feedback on their efforts, following a March meeting in Ocean City, MD.

Funded by Sea Grant programs in Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware, the project is working to connect three different models that will give communities information about how land use affects the health of coastal bays. One model calculates the movement of nutrients from land into water, a second model predicts water quality in the adjacent coastal bays, and the third model predicts eelgrass survival in the bays.

“Computer models have long been used as research and management tools in marine ecosystems, but the complexity of state-of-the-art models makes them unavailable for direct use by managers and local planners,” says Mark Brush, a VIMS associate professor and an investigator on the project. “Our goal is to develop models that can be directly used by local stakeholders in their day-to-day activities to minimize human impacts on the Delmarva coastal bays.”

“Computer models have long been used as research and management tools in marine ecosystems, but the complexity of state-of-the-art models makes them unavailable for direct use by managers and local planners,” says Mark Brush, a VIMS associate professor and an investigator on the project. “Our goal is to develop models that can be directly used by local stakeholders in their day-to-day activities to minimize human impacts on the Delmarva coastal bays.”

The research team, which also includes Lora Harris, a University of Maryland scientist, and Joanna York of the University of Delaware, began by scouring the available data and bringing together mathematical equations that calculate nitrogen loading and the response of bay water quality and eelgrass. Now, by collaborating on the design and functionality of the model suite, they hope that the final product, due out in 2015, will give end-users a tool tailored to their needs.

“The purpose of this workshop is to pull back the curtain on the models,” says Harris. For her and her collaborators, it means discussing with the intended users how the models are formulated and what they can and can’t provide.

As Harris told the room, “We need to know whether you have confidence in these data and whether they’re useful for you.”

In the end, workshop participants did just that, deciding which tweaks should be added and which should be left out.

This kind of feedback is key to the success of the models, and the online interface through which they will ultimately be delivered, says Brush. “We don’t want to create features in the models just because we want them. They have to be useful to our stakeholders.”

Brush, meanwhile, has been focusing on the mathematical and calibration aspects of the bay model. During the six months between the first and second workshops, he used real data gathered across the Delmarva seaside to check whether the equations are working. Although the management interest is in nitrogen, there are more than 7 other variables at play in the region’s 33 coastal bays. He showed workshop attendees a line graph of chlorophyll concentrations. In the middle of the graph, around June and July, the line became extremely wavy. Brush says he is still tuning the model to calibrate it for the summer months.

Other user feedback in these meetings helps to ensure the models are user-friendly, such as swapping out scientific measures, like hectares and kilograms, for locally used ones, like acres and pounds.

“I applaud these researchers and what they’re doing to make sure this product is useful,” said Troy Hartley, director of Virginia Sea Grant.

Currently, the only comparable model is the EPA-developed Bay Model, a complex computer system that can calculate how different land uses might affect runoff and nutrient loading. The system includes so many variables and equations, however, that it requires a specialist to operate it—and running one scenario may take days. While the model is useful for scientific research and regional management scenarios, it is less practical for individual communities.

“Most communities, especially small ones, don’t have the resources to build and use a Bay Model,” says Brush.

The team wanted, instead, to develop models that communities could use as planning tools. If a locality is considering a zoning change, for example, it could use the models to compare nutrient loads and the bay response under current and proposed conditions

Pilot versions of the online model allow users to adjust several features in the watershed, including land use distributions, crop distributions and fertilization rates, and population sizes. The model then makes predictions in just a few minutes.

Although much of the math is worked out, the models still need fine-tuning; responding to feedback from the workshop will be key to moving this tool to community practitioners. The team intends to continue gathering comments over the next six months and will host group test-runs of the models in early 2015 to evaluate practice scenarios and continue tweaking before the final models go online later in the year.

The Delmarva Modeling Project is a regional research effort funded by Sea Grant programs in Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware. Researchers on this project include Brush, Harris, and York.