VIMS researchers monitor harmful algal bloom

Researchers at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science continue to monitor a large but patchy bloom of harmful algae in the York River near VIMS.

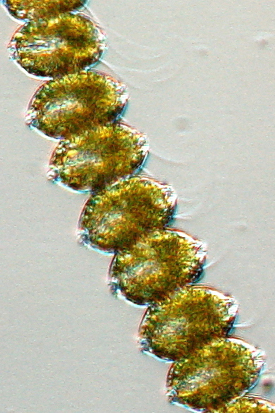

The bloom—which has been observed and sampled in the York River, the North River, and throughout Mobjack Bay—is dominated by a single-celled protozoan dinoflagellate called Alexandrium monilatum. This is a different species than Cochlodinium polykrikoides, the dinoflagellate associated with the bloom that discolored large areas of lower Chesapeake Bay in August.

The Cochlodinium bloom now seems to have died down in the York River region, though other Cochlodinium blooms persist in the lower James River near the Monitor-Merrimac Memorial Bridge, in the Elizabeth and Lafayette rivers, and near the Chesapeake Bay Bridge Tunnel.

The current A. monilatum bloom began in late August, similar in timing to the onset of A. monilatum blooms in the York River during the past few years. A. monilatum was first conclusively detected in Chesapeake Bay in 2007, when VIMS professor Kim Reece and colleagues used microscopy and DNA sequences to identify it as the dominant species of a bloom that persisted for several weeks in the York River. Earlier reports of Alexandrium in the Bay, from the mid-1940s and mid-1960s, do not clearly identify the species as A. monilatum.

The current A. monilatum bloom began in late August, similar in timing to the onset of A. monilatum blooms in the York River during the past few years. A. monilatum was first conclusively detected in Chesapeake Bay in 2007, when VIMS professor Kim Reece and colleagues used microscopy and DNA sequences to identify it as the dominant species of a bloom that persisted for several weeks in the York River. Earlier reports of Alexandrium in the Bay, from the mid-1940s and mid-1960s, do not clearly identify the species as A. monilatum.

Reece, a member of Virginia’s Harmful Algal Bloom Task Force, says the current bloom is cause for concern, but notes that there have so far been no reported fish kills or human-health effects.

She notes that any questions related to the bloom’s possible effects on human health should be addressed to the Virginia Department of Health via Virginia's toll-free Harmful Algal Bloom hotline at 888-238-6154. The line is available 24-7.

Alexandrium monilatum is a chain-forming dinoflagellate that has been reported for decades in blooms along the Gulf Coast and the southeastern U.S. coast, primarily in Florida, where it has been found associated with fish and shellfish kills.

The organism is known to produce a toxin called goniodomin A, but the toxin’s potential impacts to marine life and human health remain largely unknown. Experiments done in the laboratories of Reece and professor Wolfgang Vogelbein at VIMS have demonstrated that exposure to A. monilatum cells, both whole and broken, causes mortality in their test organisms, the brine shrimp Artemia salina and larvae of the native eastern oyster Crassostrea virginica.

VIMS scientists have also experienced impacts to experimental animals exposed to York River water during blooms. Large numbers of Rapa whelks in flow-through aquaria died during the bloom of 2007, and during the summer of 2008 a similar die-off of cownose rays occurred.

York River Sampling

Reece and colleagues continue to monitor the bloom's distribution and density, which have varied widely over the last few days.

"We were out on Friday afternoon [August 30]," says Reece, "and found dense patches of A. monilatum near the Goodwin Islands with long chains of cells reaching counts of more than 7,000 cells per milliliter." A 1-liter soda bottle holds 1,000 milliliters.

“The bloom has been very patchy,” adds Reece. “Tides, winds, and vertical migration are all playing a role. We’re seeing high variation among the samples, even between those that were collected from sites a few hundred yards apart or taken from the same site a few hours apart."

Reece reports that bioluminescence has also been observed recently in local waters. "We recently collected a sample from Sarah's Creek where bioluminescence is occurring," she says, "and have confirmed that it associated with the sexual stage of Alexandrium."