Bay grasses up but below goal

An annual aerial survey led by researchers at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science shows that underwater grasses covered 85,899 acres of Chesapeake Bay and its tidal rivers in 2009. This was a 12 percent increase from 76,860 acres in 2008 and the highest baywide acreage since 2002. The 2009 SAV abundance represents a 46% attainment of the 2010 restoration target of 185,000 acres set by the Chesapeake Bay Program.

Bay grasses—also called submerged aquatic vegetation or SAV—are critical to the Bay ecosystem because they provide habitat and nursery grounds for fish and blue crabs, serve as food for animals such as turtles and waterfowl, clear the water, absorb excess nutrients, and reduce shoreline erosion. Bay grasses are also an excellent measure of the Bay's overall condition because they are not under harvest pressure and their health is closely linked to water quality.

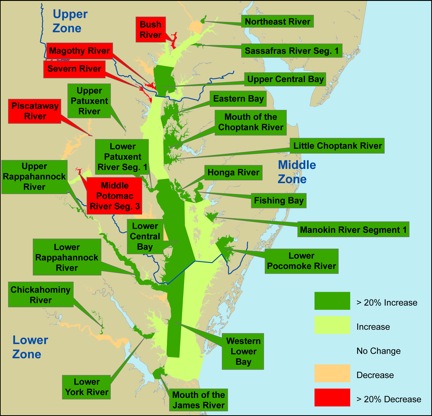

VIMS professor Bob Orth, leader of the SAV baywide annual survey, says "The overall increase in SAV acreage in 2009 was strongly driven by changes in the middle and lower Bay zones, including Tangier Sound, the lower central and eastern lower Chesapeake Bay, Mobjack Bay and the Honga, Rappahannock, and lower Pocomoke rivers."

Bay grass acreage increased in all three of the Bay's geographic zones—upper, middle and lower—for just the second time since 2001.

Upper Bay

In the upper Bay zone (from the Chesapeake Bay Bridge north), bay grasses covered about 23,598 acres, just shy of the 23,630-acre goal for this geographic zone and a 3 percent increase from 2008. Large percentage increases were observed in the Northeast River, part of the Sassafras River and the upper central Chesapeake Bay, an area just north of the Bay Bridge. However, bay grass acreage in a few local rivers, such as the Bush and Magothy, decreased significantly and offset increases elsewhere. Overall, the massive grass bed on the Susquehanna Flats continues to dominate this zone.

"The growth and persistence of the SAV bed in the Susquehanna Flats—including the largest bed in the Bay—continues to be a major success story for bay grass recovery today," said Lee Karrh, living resources assessment chief with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources and chair of the Bay Program's SAV Workgroup. "Many of the Bay's lower salinity areas are doing well and seem to be driven by reductions in nutrient pollution entering the Bay. Seventeen segments in this zone have met or exceeded their restoration targets."

Middle Bay

In the middle Bay zone (from the Chesapeake Bay Bridge to the Potomac River and Pocomoke Sound), bay grass acreage increased 15 percent to 39,604 acres, 34 percent of the 115,229-acre goal. Eighty-four percent of the acreage increase in the middle Bay zone occurred in five segments: Eastern Bay, the Honga River, Pocomoke and Tangier sounds, and the lower central Chesapeake Bay. These changes reflect a large expansion of widgeon grass—the dominant SAV species in this zone—as well as the continued recovery of eelgrass in Tangier Sound. Elsewhere in the middle Bay zone, large percentage declines in bay grass acreage were observed in the Severn River and Piscataway Creek, a tributary of the Potomac River.

Lower Bay

In the lower Bay zone (south of the Potomac River), researchers mapped 22,697 acres of bay grasses—a 17 percent increase from 2008 and 49 percent of the 46,030-acre restoration goal. This is the third year that bay grasses in the lower Bay zone have increased since 2005, when hot summer temperatures caused a dramatic large-scale dieback of eelgrass. Eighty-two percent of the acreage increase in the lower Bay zone occurred in Mobjack Bay, the lower Rappahannock River and the eastern lower Chesapeake Bay. Improvements in the lower Rappahannock River were due to an increase in widgeon grass, while in Mobjack Bay and the eastern lower Chesapeake Bay, eelgrass recovery was the reason for percentage gains. None of the 28 segments in the lower Bay zone saw large declines in bay grasses in 2009.

"We are cautiously optimistic about eelgrass recovery now that it is into its third year following the 2005 dieback," said Orth. "But we are concerned about the long-term absence of eelgrass from areas that traditionally supported large dense beds, such as much of the York and Rappahannock rivers, many of the mid-bay areas just north of Smith Island, and in the deeper areas of Pocomoke Sound. Declining water clarity noted in much of the lower Bay may be a major impediment to eelgrass recovery."

Annual bay grass acreage estimates are an indication of the Bay's response to pollution control efforts, such as implementation of agricultural best management practices (BMPs) and upgrades to wastewater treatment plants. Bay watershed residents can do their part to help bay grasses by reducing their use of lawn fertilizers, which contribute excess nutrients to local waterways and the Bay, and participating with their local tributary teams or watershed organizations.

Bay grass acreage is estimated through an aerial survey, which is flown from late spring to early fall. For additional information about the aerial survey and an interactive map of SAV acreage throughout the Chesapeake Bay, visit www.vims.edu/bio/sav/.

For more information about the status of underwater bay grasses in the Chesapeake Bay, visit the Chesapeake Bay Program website. The Chesapeake Bay Program is a regional partnership that has coordinated and conducted the restoration of the Chesapeake Bay since 1983. Partners include the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; the U.S. Department of Agriculture; the states of Delaware, Maryland, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia; the District of Columbia; the Chesapeake Bay Commission, a tri-state legislative body; and advisory groups of citizens, scientists and local government officials.