The comeback continues for Virginia’s bay scallops

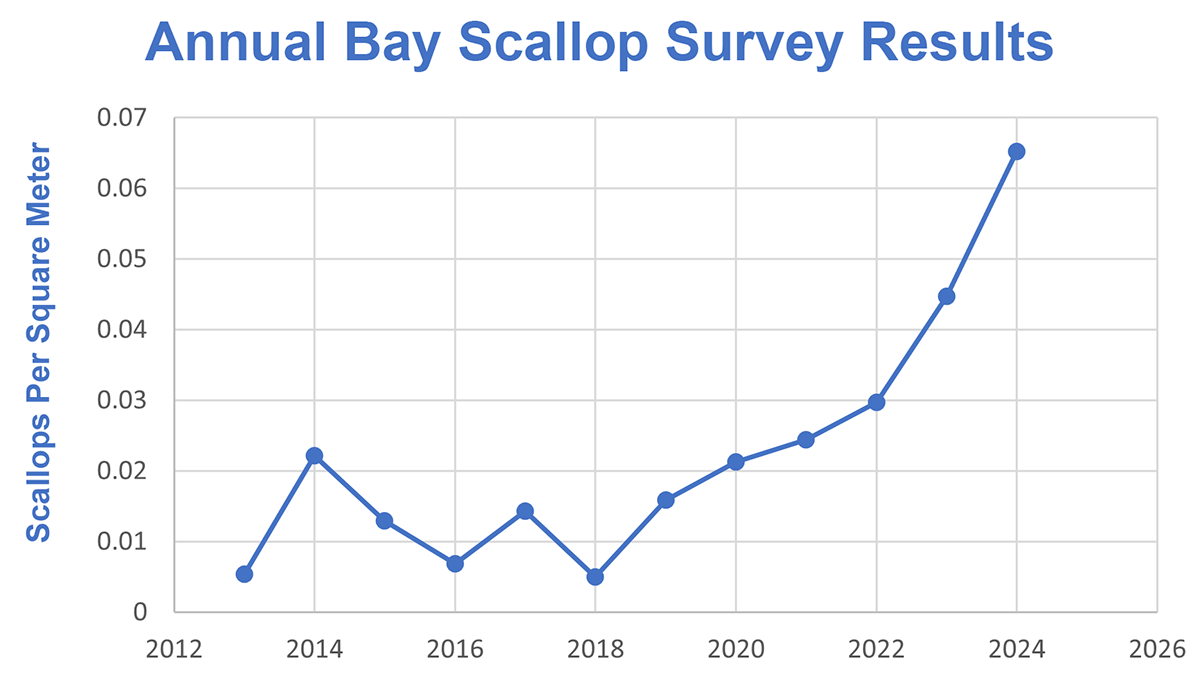

Once locally extinct, bay scallops along Virginia’s Eastern Shore appear to be making a comeback. After several years of exponential growth, the results of the annual population survey show the density of bay scallops in southern coastal bays has reached nearly 0.07 scallops per square meter.

Scientists at William & Mary's Batten School & VIMS led the survey and have been working to restore the population of bay scallops in Virginia's coastal bays since 2012.

This may not be enough to support a recreational fishery, but it could be close. For reference, Florida sets a minimum population density of one bay scallop per 10 square meters (0.10 scallops per square meter) to regulate its recreational fishery.

Bay scallops were once part of Virginia’s seaside marine environment, protected behind the barrier islands in lush underwater grass meadows. A commercial fishery existed in the early 1900s until an eelgrass wasting disease destroyed grass beds along the East Coast, eliminating essential habitat for the species.

The most successful seagrass restoration effort in the world

In 2001, former Director of the Submerged Aquatic Vegetation (SAV) Program at the Batten School & VIMS Robert Orth began a seagrass restoration project after a small patch of eelgrass was discovered in 1997 in South Bay near Wreck Island. Continued by his successor and current SAV Program Director Christopher Patrick, this effort has resulted in the largest restoration of seagrass in the world.

By 2010, VIMS, in partnership with The Nature Conservancy (TNC), the University of Virginia, and other partners, had restored approximately 6,000 acres of underwater meadows. It was now time for the ESL team to utilize its expertise in aquaculture to bring back the bay scallop.

The ESL has a long history specializing in shellfish aquaculture. It’s founding director, Mike Castagna, helped establish Virginia’s hard clam industry—now the largest in the U.S.—with research in the 1960s. Castagna also started working on bay scallop aquaculture.

In 2010, former ESL Director and current Associate Dean for Research and Advisory Services Mark Luckenbach brought wild scallops from North Carolina to the ESL’s Castagna Shellfish Research Hatchery. In 2012, they began releasing bay scallop larvae, juveniles and adults into the restored grass beds. This started the bay scallop restoration project, and the annual survey started in 2013 to track their population.

Conducting the survey

The survey is no small feat, growing in scope with the expansion of the underwater grass meadows. Over the course of three days, a small army of scientists, staff, and volunteers split up approximately 240 stations located throughout the Eastern Shore’s southern coastal bays. Boats are manned by a minimum of five people. Once at a station, the surveyors radiate out from their boat, each placing a one-square-meter quadrat in water up to four feet deep and using their hands to feel for scallops hiding in the grass within the quadrat. As a group, they repeat this process 50 times at each station, ultimately searching more than 12,000 square meters of seagrass meadow by hand. Scallops are counted, measured and a small subset are brought back to the ESL for DNA sampling and to use as brood stock for future generations while the rest are released back into the wild.

“It's a multi-institution, multi personnel, all-hands-on-deck activity, and something we look forward to every year with dread and excitement because it is a lot of work, but it's also extremely exciting and rewarding to do,” said Snyder.

The researchers also record similar data about another bivalve group, Ark clams, along with the water depth, sample time and the density of the grass at each station.

To date, approximately 10,000 acres of seagrasses have been restored. The ultimate goal is to reestablish grass beds from Fisherman’s Island in the south all the way up to Chincoteague, but it will require continued and expanded funding. The efforts have been supported by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration grants through the Virginia Coastal Zone Management program and the Saltonstall-Kennedy Grant program, the Army Corps of Engineers, the Keith Campbell Foundation and individual private donors.

Answering the genetics question

The first several years of scallop restoration efforts were tumultuous. Initial hopes were dashed when populations crashed in subsequent years. This boom-bust trend continued for the first five years, prompting the team to consider the genetic diversity of the species.

It's unclear whether the increased genetic diversity was the reason for the turnaround or if the population had finally reached a threshold required for sustained growth.

“We’re trying to figure out what the Virginia scallop looks like genetically. We really don’t know what the genetics were originally since they were lost so long ago, but we suspect they were a blend of characteristics from scallops that live in cooler, northern climates and more heat-tolerant, southern variants,” said Snyder.

Batten School Ph.D. student Leslie Youtsey is working on an answer to the genetics puzzle. Working with co-advisors Synder and Batten School Associate Professor Jan McDowell, Youtsey is performing DNA analyses on scallops collected from the annual surveys and used for aquaculture farming. The ESL team is also working to isolate DNA from scallop shells located at commercial sites from the early 1900s.

As they attempt to answer these questions, the team is encouraged by the sustained population growth in recent years.

“At some point, we’ll need to pull back our support to determine whether the population can continue to expand on its own,” said Snyder.

Supporting the aquaculture industry

While the ESL attempts to increase the resilience of wild bay scallops through expanded genetic diversity, they are also homing in on ideal traits for an aquaculture environment. Each growing season, they provide small juveniles as “seed” to local farmers to test in commercial operations.

“We’re hoping to prove that the bay scallop can be easily added to an aquaculture farm without having to significantly change operations,” said ESL Hatchery Manager Rebecca T. Smith. “It's been really rewarding to see a lot of interest pick up from the local local growers. We had more people requesting test seed this year than ever before.”

“We’ve isolated a genetic line that produces some very distinct orange scallops, and there are other variations that include reds, browns and stripes. We hope to swap our orange scallops for a yellow line that has been isolated in North Carolina so we can start breeding pure color lines,” said Smith. “This isn’t something that we’d want to do for a restoration project for wild scallops, but we can make a more visually appealing product for aquaculture farms.”

Nearly 100 years after they disappeared from Virginia, bay scallops are finally making a comeback both in the wild and on the dinner plate. VIMS will continue to apply its expertise to support both the restoration of the wild population and the burgeoning aquaculture industry. The coming years will be pivotal for the species.

“Being able to get these animals through the nursery phase and hold them in your hands—just these piles of scallops—it's beyond rewarding. I can't even describe it,” said Smith. “But, to see the wild population continuing to climb over the past few years is just incredible. I'm really grateful to be a small part of that effort.”